Intro to Self-Publishing: Showcasing Student Work in Print Date: October 19th, 2019 Time: 8am - 5pm Location: Lake Stevens School District Early Learning Center, Community Room Address: 9215 29th St. NE Lake Stevens, WA 98258 Clock Hours: 8 hours Cost: Free! Self-publishing offers great opportunity to create print-on-demand books at surprisingly low cost, and it’s easier than you might think! This free full day workshop will give you the tools you need to get started, as well as the hands-on time to practice and decide how you want to use publishing in your own classroom. Whether you want to publish your students work for them or use book publishing as project-based learning, this workshop will get you started.

Participant Requirements:

Study Participation This workshop is being offered as part of the instructor’s master’s degree capstone project, and as such it also includes an option to participate in a simple research study. If you opt to participate, you will be asked to complete a simple 10 question multiple choice test and a simple 10 question survey, before and after instruction.  Instructor Bio Caitlin McQuinn has a unique combination of backgrounds in technology, publishing, and educational technology. She worked in Apple retail through college and after, teaching workshops and later working in tech support behind the “Genius Bar.” After leaving Apple, Caitlin worked in the world of self-publishing, creating a small business out of republishing her grandfather’s out-of-print novels, releasing books in print and digital formats. Through all of this Caitlin often volunteered her assistance at education technology workshops. She herself has also taught workshops on maker education topics, from low tech to higher tech, and has co-run NCCE Maker Camp for the last three summers. After graduating, Caitlin will be pursuing opportunities that will allow her to split her time between teaching in a classroom and developing future workshops and other exciting programs.

0 Comments

We’re working with NCCE to put on our third summer of Maker Camps this coming August. (Read all the details here!) I’m not sure of the exact count, but this will make about fifteen NCCE camps that we’ve offered at Pack Forest in the last dozen years. Holding a professional development program as an overnight camp adds a lot of challenges. It means dealing with overnight accommodations for all the participants, arranging meals, and transporting all equipment and supplies necessary because we’re about 90 minutes away from home in Burien. (We had so much to haul last year we actually needed to rent a van.) So if there’s that much hassle involved, why do it?  Because setting matters! We will have great instructors and sessions, of course, but they are also enhanced by the location. Pack Forest is a relaxing, beautiful facility outside of Eatonville. The buildings are rustic, surrounded by tall fir trees and little else. Delicious meals are provided, so for the two days for each camp participants can simply concentrate on learning and networking with others. Freed from the distractions of being home (at least for one night!), it provides a chance to focus more deeply than is normally possible in a regular workshop model. It seems pretty logical that people learn better when they’re comfortable and relaxed, and our experience with these camps indicates it’s definitely true. Many years ago I heard a researcher speak on the connection between emotions and learning, and one of his quotes stuck with me: “In an atmosphere of ecstasy, learning is not only enhanced, it is inevitable.” I won’t go so far as to say our Maker Camp will be an ecstatic experience, but they certainly will be a lot of learning and a lot of fun! Budget-Friendly Makerspaces is August 6-7, and Tech-Ful Makerspaces is August 8-9. For complete camp descriptions and registration, go here!  I recently saw a Facebook posting from an organization I respect that recognized Chief Sealth as the namesake of Seattle. I am very much in support of this, but there was a problem. It was illustrated with this photograph on the left. This is not Chief Sealth. I know that for several reasons:

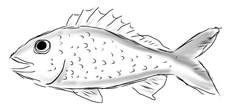

I emailed the organization that posted the original image, and they quickly corrected it and apologized for misrepresenting such an important figure. It’s easy to understand how they made the mistake, however. If you do an image search for Chief Seattle/Sealth, you’ll see this image will feature prominently in your results. Misinformation spreads easily on the Internet. This is why I quibble with those who say things “Kids shouldn’t have to learn anything they can Google.” I was able to recognize this image was wrong because I had learned stuff, and I could use the information I already knew to interpret and evaluate the original posting. In order to do an effective search and sort the results, you have to have pre-existing knowledge. Memorization is still part of learning. This was further reinforced by my attempts to figure out just who the man in the striking image actually is. I downloaded the image and uploaded it into the Google “Search by Image” function. There were many, many hits, and those that weren’t mistakenly labeled Chief Sealth instead identified him as Chief Black Kettle of the Cheyenne tribe. I looked at several of the sites and came away confident that this was correct. However… The next day I was discussing this with a colleague and was ready to tell him who the image was, but I had a moment of doubt. So I went to the Wikipedia page for Black Kettle, and while there were a few photographs of him, the image I had used for the search was not among them. When I checked his biographical information, I found he been killed in 1868. The image was from the wrong era and couldn’t be him. Did I find who the image actually represents? Yes, but I’m not going to tell you who it is. I’m going to challenge you to do your own “Search by Image,” so you can see how many incorrectly labeled versions of this image you have to wade through. (It’s worth the effort, for the man in the photograph is a fascinating figure who lead an amazing life.) My main point here is that when I see lists of the skills that kids need in order to navigate information on the web, I never see anyone listing that students need to have a body of content that they have learned. The volume of misinformation on the Internet is growing minute by minute, much of it shared with malicious intent. (Russia alone generates thousands of media postings per month with specific intent to drown out factual information.) People who wade into this increasingly polluted body of information need to be armed with basic knowledge of science, history, and other core content in order to to ask intelligent questions and develop the necessary BS filters to interpret what they see and get to the actual truth.  The last two or three years have shown how powerful social media has become in our society. We’ve all been shocked to see how quickly and deeply Twitter, Facebook, and similar tools have worked their way into our individual lives and our culture at large. From a neuroscience perspective, however, it’s not surprising at all. Our brains crave novelty. Discovering something new and interesting triggers a happy little reward circuit, and social media is a never-ending stream of interesting things. Our brains are also wired to make social information one of our highest priorities, so having a never-ending stream of new and interesting social content at our fingertips is naturally extremely engaging. The surprise then isn’t that social media has had a large influence on us, but rather that we didn’t see it coming. (Actually, some did: I heard David Thornburg say this almost twenty years ago: “People keep saying we’re in the Information Age. We’re not. We’ve passed through the Information Age into the Communication Age. We need to understand the difference.”) What also shouldn’t be surprising is that there are people, businesses, and organizations that have become masterful at using neuroscience to create social media that is very powerfully manipulative. We’ve all seen “clickbait” titles that prey on our curiosity like You won’t believe what happened next! While annoying, these are mainly harmless tricks in a media world competing for you attention. In the last few years, however, we’ve seen more and more items like Senator Belfry Advocates Eating Live Puppies, where the goal is to trigger a fearful and/or outraged response – and widespread sharing. If you’re seeking to manipulate people, outrage and fear are very helpful tools. When these are strong enough, they will trigger your emotional system to a level that significantly impedes your ability to think. You go into a reactive mode rather than reflective state, and you feel like you just have to do something. People can be motivated to say things and act in ways they normally wouldn’t. (We’ve all had the experience of being in an argument and saying or doing something that we not only regretted, but afterwards didn’t even make sense to ourselves.) If you are a regular user of Facebook or Twitter, think about how many of the messages you see that are framed to be upsetting. Many political messages in particular are built around outrage or fear. Even more troubling, many of the groups or individuals who create this content have figured out that it simply doesn’t matter if it’s true or not – people will click on it, read it, and share it regardless. A visit to www.snopes.com to read the Hot 50 stories will show how prevalent false stories are. (As of the time I’m writing this, only nine of the “Hot 50” articles are actually true.) We have a situation where there is a strong financial return for creating upsetting stories that feed into people’s pre-existing biases, and it’s a lot easier and cheaper to make up stories than to research real ones. And the situation will only get worse. This posting was inspired by a tweet from Michelle Zimmerman (@mrzphd) about the subject of a presentation by writer Zeynep Tufecki (@zeynep): Every time you use Machine Learning, you don’t know exactly what it’s doing. YouTube has found out that finding more extreme content keeps people engaged, like conspiracy, extreme politics. Our social media and news feeds are increasingly managed by artificial intelligence and machine learning systems, which constantly monitor what gets and holds attention best. They combine the big data of the whole population of users with our own individual patterns to fine-tune exactly what should keep us most engaged. This AI doesn’t care about the nature of the content, whether it’s true, or whether it’s good or bad for you or society at large. It only cares about your attention. And AI will get more powerful at doing this every single day. I want to be clear that I’m not saying social media and AI are bad. After all, this is a social media post inspired by other social media posts, and AI is an exciting topic for students and responsible for some amazingly positive things. (Michelle Zimmerman, mentioned above, has written a book for ISTE on the topic – http://iste.org/TeachAI) . What I am saying, however, is that part of digital literacy for our students has to be learning how to understand the manipulative power of social media can be used against them, and how they can use that knowledge to both protect themselves and to avoid becoming manipulators. We should do is to stop teaching social-emotional learning and digital literacy as separate topics. For many (if not most) of our students, their social-emotional lives and their smartphones are inseparable. Many SEL programs and digital literacy programs already touch on this, but I think the last few years have demonstrated it needs to be emphasized much more strongly. When we teach students about social-emotional learning, part of their learning needs to be the application of this knowledge to their use of digital media. If they understand how social media sources use their emotions to manipulate them, they can be better equipped to resist it. Likewise, they can hopefully use this knowledge to make informed, more positive decisions on what they post and share themselves, and be part of the solution rather than part of the problem. Our students will spend their entire lives in a world where social media and machine learning are ubiquitous. We need to help give them control over these technologies, so it's not the other way around.  For most educators, September is the crazy-busiest month of the year. For someone involved in professional development, though, it's down time. After go full-out for the latter part of July and all through August, the busy training season shuts down the day school starts. September for me is like summer break, only with a lot less sunscreen. And more sweaters. It's given me some time to reflect on our summer projects, and in particular the second summer of Maker Camps that Caitlin and I hosted for NCCE at the wonderful Pack Forest Conference Center in Eatonville. We held two sessions, with an introductory camp on August 7 & 8, and a camp for more experience participants on August 9 & 10. About fifty educators participated, with a sizable number signing up for the two camps back-to-back. Fourteen amazing instructors offered a range of sessions (here and here), including topics as diverse as design thinking, programming microcontrollers (such as Arduino and BBC Micro:Bit), 3D printing, connecting Making to the NGSS standards, and Making with simple materials. We also held extended evening “open labs,” where participants could spend time exploring and working with whichever tool, materials, or software they wanted. It was four busy, exciting days of activity. A camp setting can provide a different kind of professional development than educators can normally experience. Where many conferences or institute can often be a dizzying series of shorter sessions, we worked to give teachers the opportunity to spend a significant amount of time working in the same mode that their students should. Making should engage learners in extended, focused exploration work with significant amounts of self-direction and agency. Put another way, if there’s no play, it’s not Making. (The NCCE conference does a lot of this, too!) There’s a Latin phrase* that sums up the philosophy of our camps: Nemo dat non quad habet. It translates “You can’t provide what you don’t have.” Teachers can’t provide what they don’t have, either. Professional development experiences should reflect what the students will experience. Imagine an ideal classroom, where students are enthusiastically engaged in focused, challenging work that stretches their skills, knowledge, and creativity. They’re so self-directed that the teacher can just quietly circulate and provide assistance and advice on an as-needed basis. If that’s what we want in a classroom, that’s what the professional development should look like, too. Don’t get me wrong. There are certainly times in both classrooms and professional development where direct instruction is appropriate, and research shows that even good old-fashioned lectures for some situations can be the most effective approach. I do presentations all the time. But it’s also kind of the default, and it can feel deceptively time-efficient because we can cover so much information so quickly. But it’s only efficient if the learners actually learn, and too much content is just the same as too little. It simply won’t stick for most students. And direct instruction is never a good way to teach skills if we don’t give ample time (hopefully with the instructor present) to practice. So that’s why we design our camp that way, as well as other trainings we’ve done. Plus, it’s kind of a dirty little secret, but I long ago discovered that it’s much, much easier to prepare and teach an engaging six-hour project-based workshop than a 50-minute conference presentation. And I feel like the participants come away with a far greater likelihood of applying what they learned than if I had lectured to them for the same amount of time. And as the instructors, we always learn a lot more that way, too! Interested in participating in our camps next summer or want updates on any upcoming workshops? Sign up for our newsletter! It will only be published every month or two, because you don't need more email, and we're not that talkative. *The real legal meaning of the term is written up here. But I’m still going to use it my way.  As a follow-on to my last blog post, I want to point to a bit of 19th-century teaching wisdom that seems very appropriate for our 21st-century world. About thirty years ago a friend gave me a photocopy of an essay called The Student, the Fish, and Agassiz. I enjoyed it so much that I filed it away, and I have referenced it many times over the years in presentations and discussions. (Thanks, Ran!) It is a recollection written in 1879 by a former student of the Harvard scientist Louis Agassiz. Like many good stories, the core idea has application in many settings. My copy had an introduction framing it as way to explore the Bible, and you will find many websites featuring the story (or adaptations of it) in that context. I have often used it as an example with educators of what I think deep learning should look like, and how rarely we provide students with the kind of experience described in the essay. In the years since I was given my copy, the Internet has made it possible to access the same article online, rather than me having to dig through my files for the now dog-eared original. Unfortunately, it has also made it possible to find multiple versions that have been edited or reworked to either "update" it or to make it shorter, which given the point of the story seems oddly ironic. The version online that seems to be the unaltered original can be found here, but given the ephemeral nature of the Internet, I'm pasting a copy below in case that page goes glimmering. I hope you enjoy as much as I have. The Student, the Fish, and Agassiz by the Student [Samuel H. Scudder] It was more than fifteen years ago that I entered the laboratory of Professor Agassiz, and told him I had enrolled my name in the scientific school as a student of natural history. He asked me a few questions about my object in coming, my antecedents generally, the mode in which I afterwards proposed to use the knowledge I might acquire, and finally, whether I wished to study any special branch. To the latter I replied that while I wished to be well grounded in all departments of zoology, I purposed to devote myself specially to insects. "When do you wish to begin?" he asked. "Now," I replied. This seemed to please him, and with an energetic "Very well," he reached from a shelf a huge jar of specimens in yellow alcohol. "Take this fish," he said, "and look at it; we call it a Haemulon; by and by I will ask what you have seen." With that he left me, but in a moment returned with explicit instructions as to the care of the object entrusted to me. "No man is fit to be a naturalist," said he, "who does not know how to take care of specimens." I was to keep the fish before me in a tin tray, and occasionally moisten the surface with alcohol from the jar, always taking care to replace the stopper tightly. Those were not the days of ground glass stoppers, and elegantly shaped exhibition jars; all the old students will recall the huge, neckless glass bottles with their leaky, wax-besmeared corks, half-eaten by insects and begrimed with cellar dust. Entomology was a cleaner science than ichthyology, but the example of the professor who had unhesitatingly plunged to the bottom of the jar to produce the fish was infectious; and though this alcohol had "a very ancient and fish-like smell," I really dared not show any aversion within these sacred precincts, and treated the alcohol as though it were pure water. Still I was conscious of a passing feeling of disappointment, for gazing at a fish did not commend itself to an ardent entomologist. My friends at home, too, were annoyed, when they discovered that no amount of eau de cologne would drown the perfume which haunted me like a shadow. In ten minutes I had seen all that could be seen in that fish, and started in search of the professor, who had, however, left the museum; and when I returned, after lingering over some of the odd animals stored in the upper apartment, my specimen was dry all over. I dashed the fluid over the fish as if to resuscitate it from a fainting-fit, and looked with anxiety for a return of a normal, sloppy appearance. This little excitement over, nothing was to be done but return to a steadfast gaze at my mute companion. Half an hour passed, an hour, another hour; the fish began to look loathsome. I turned it over and around; looked it in the face -- ghastly; from behind, beneath, above, sideways, at a three-quarters view -- just as ghastly. I was in despair; at an early hour, I concluded that lunch was necessary; so with infinite relief, the fish was carefully replaced in the jar, and for an hour I was free. On my return, I learned that Professor Agassiz had been at the museum, but had gone and would not return for several hours. My fellow students were too busy to be disturbed by continued conversation. Slowly I drew forth that hideous fish, and with a feeling of desperation again looked at it. I might not use a magnifying glass; instruments of all kinds were interdicted. My two hands, my two eyes, and the fish; it seemed a most limited field. I pushed my fingers down its throat to see how sharp its teeth were. I began to count the scales in the different rows until I was convinced that that was nonsense. At last a happy thought struck me -- I would draw the fish; and now with surprise I began to discover new features in the creature. Just then the professor returned. "That is right," said he, "a pencil is one of the best eyes. I am glad to notice, too, that you keep your specimen wet and your bottle corked." With these encouraging words he added -- "Well, what is it like?" He listened attentively to my brief rehearsal of the structure of parts whose names were still unknown to me; the fringed gill-arches and movable operculum; the pores of the head, fleshly lips, and lidless eyes; the lateral line, the spinous fin, and forked tail; the compressed and arched body. When I had finished, he waited as if expecting more, and then, with an air of disappointment: "You have not looked very carefully; why," he continued, more earnestly, "you haven't seen one of the most conspicuous features of the animal, which is as plainly before your eyes as the fish itself. Look again; look again!" And he left me to my misery. I was piqued; I was mortified. Still more of that wretched fish? But now I set myself to the task with a will, and discovered one new thing after another, until I saw how just the professor's criticism had been. The afternoon passed quickly, and when, towards its close, the professor inquired, "Do you see it yet?" "No," I replied. "I am certain I do not, but I see how little I saw before." "That is next best," said he earnestly, "but I won't hear you now; put away your fish and go home; perhaps you will be ready with a better answer in the morning. I will examine you before you look at the fish." This was disconcerting; not only must I think of my fish all night, studying, without the object before me, what this unknown but most visible feature might be, but also, without reviewing my new discoveries, I must give an exact account of them the next day. I had a bad memory; so I walked home by Charles River in a distracted state, with my two perplexities. The cordial greeting from the professor the next morning was reassuring; here was a man who seemed to be quite as anxious as I that I should see for myself what he saw. "Do you perhaps mean," I asked, "that the fish has symmetrical sides with paired organs?" His thoroughly pleased, "Of course, of course!" repaid the wakeful hours of the previous night. After he had discoursed most happily and enthusiastically -- as he always did -- upon the importance of this point, I ventured to ask what I should do next. "Oh, look at your fish!" he said, and left me again to my own devices. In a little more than an hour he returned and heard my new catalogue. "That is good, that is good!" he repeated, "but that is not all; go on." And so for three long days, he placed that fish before my eyes, forbidding me to look at anything else, or to use any artificial aid. "Look, look, look," was his repeated injunction. This was the best entomological lesson I ever had -- a lesson whose influence was extended to the details of every subsequent study; a legacy the professor has left to me, as he left it to many others, of inestimable value, which we could not buy, with which we cannot part. A year afterwards, some of us were amusing ourselves with chalking outlandish beasts upon the blackboard. We drew prancing star-fishes; frogs in mortal combat; hydro-headed worms; stately craw-fishes, standing on their tails, bearing aloft umbrellas; and grotesque fishes, with gaping mouths and staring eyes. The professor came in shortly after, and was as much amused as any at our experiments. He looked at the fishes. "Haemulons, every one of them," he said; "Mr. ____________ drew them." True; and to this day, if I attempt a fish, I can draw nothing but Haemulons. The fourth day a second fish of the same group was placed beside the first, and I was bidden to point out the resemblances and differences between the two; another and another followed, until the entire family lay before me, and a whole legion of jars covered the table and surrounding shelves; the odor had become a pleasant perfume; and even now, the sight of an old six-inch worm-eaten cork brings fragrant memories! The whole group of Haemulons was thus brought into review; and whether engaged upon the dissection of the internal organs, preparation and examination of the bony framework, or the description of the various parts, Agassiz's training in the method of observing facts in their orderly arrangement, was ever accompanied by the urgent exhortation not to be content with them. "Facts are stupid things," he would say, "until brought into connection with some general law." At the end of eight months, it was almost with reluctance that I left these friends and turned to insects; but what I gained by this outside experience has been of greater value than years of later investigation in my favorite groups. -- from American Poems (3rd ed.; Boston: Houghton, Osgood & Co., 1879): pp. 450-54.  Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World by Cal Newport is not a book written for educators, but it is one that I found extremely interesting and timely. Newport is a college professor and writer, and to give a peek into his background, his previous books are How to Become a Straight-A Student, How to be a High-School Superstar, How to Win at College, and So Good they Can't Ignore You. To say that he is focused on achievement would obviously be an understatement, and you might expect that in his writing that he would come across as some sort of driven maniac. He doesn't. Instead, Newport lays out a very reasonable case for changing how we approach work. He shares neuroscience and examples illustrating the importance of extended focus and attention, and the impact of constant distraction. Some of my key takeaways are:

Several years ago, my friend and colleague Dr. Kieran O’Mahony introduced me to a concept that has shifted my thinking about how we support teachers and students. It’s also an interesting example of how a slight change in language can create a new way of looking at things.

Kieran referred to the work of researchers Giyoo Hatano and Kayoko Inagaki (and later included in John Bransford’s How People Learn) on how we look at expertise. Traditionally, this has been a term that simply described an individual’s skills and knowledge in a particular area. Hatano and Inagaki described two separate classes of expertise, however – routine expertise and adaptive expertise. They are very different. Routine expertise is the mastery of a fixed skill, where you essentially do the same thing, but with increased accuracy and efficiency. Think of playing the guitar, bricklaying, ski jumping, or any of thousands of jobs and avocations. Adaptive expertise, on the other hand, is the ability to take on a new challenge or task that you’ve never seen before. It still requires skills, knowledge, and experience, but also the ability to learn new skills, find new knowledge, and create new solutions in the face of new problems. Being able to be innovate is a basic skill needed for adaptive expertise. I think this model helps to explain why so many efforts to improve education fall flat. Many professional development programs seem to operate on the assumption that teaching is a routine expertise, and that simply by practicing and repeating those skills (hopefully under effective guidance), teachers will get better at what they do and student success will increase. The problem is that teaching is an adaptive expertise. The conditions in classrooms are constantly changing, whether it’s new curriculum, new standards, or new administrative priorities. Every group of students is different, and often individual students appear in our classrooms with experiences or needs we’ve ever seen before. Good teachers don’t simply do the same thing over and over, but instead know how to adapt every day to meet the ever-changing needs of their students and demands of their profession. It’s not strictly either/or, of course. Some aspects of running a well-organized classroom are indeed routine, such as (obviously) developing good classroom routines. I was definitely better at classroom organization after a year of practice and guidance from Mary, my wonderful facilitating teacher years ago. But teachers also need to be adaptable, and to make whatever modifications are needed to meet their students where they are on any given day. This concept has become the thread that ties together many of the initiatives I find so compelling – neuroscience in learning, personalized learning, culturally responsive learning, Maker education, design thinking, and STEM/STEAM. Innovating, monitoring, revising, and adjusting are integral to all of these models, with a focus on empowering both teachers and students to take ownership of their learning. It also makes a powerful lens for examining coaching and professional development. The support a teacher needs to develop routine expertise is very different than what they need to develop adaptive expertise. Perhaps most importantly of all, we want students to have the opportunity to develop these skills. In order for that to happen, teachers need to be able to practice them. I work the phrase “You cannot provide what you do not have” into just about every workshop or presentation. (For you Latin buffs, the original Roman quote is Nemo dat non quod habet.) Whatever kind of experience we want students to have needs to mirror what teachers do. It won’t work to have students spend every day watching adults that aren’t empowered to be flexible and innovative professionals. Wikipedia has a great overview of this topic at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adaptive_expertise You can see what Kieran is up to with neural education at http://neuraleducation.com/  I read with interest the recent news that the French Minister of Education is banning smartphones from schools for students under 15 starting next fall. (You can read about it here.) After spending the last ten years learning about what neuroscience can tell us about how the brain works, I find myself squarely on his side. That's less heretical for an ed tech person to say than it used to be. People are increasingly aware of how devices such as smartphones and the social media/communications software that drive their use are consciously designed to tap into important, basic human responses. The engineers that develop and program them are intentionally creating engines of distraction and habituation, which should come as no surprise to anyone spending any time around smartphone users, young or old. I know there are many powerful functions and apps that can make for great classroom applications. Most smartphones are more powerful than the classroom computers our students were using just a few years ago. The problem is that all of the negative, distracting aspects of the phones are an inseparable part of the package. Whether it's text messages, Twitter, Instagram, SnapChat, WhatsApp, Facebook, or whatever new things are out this month, there will be a steady stream of alerts, buzzes, dings, and other fiendishly effective distractors that will grasp for the student's attention. It's even more intense for adolescents, as they are developmentally focused on their social world, and smartphones provide an intense connection into every member of their community, all at once, all the time. This is not saying that students lack will power. It's admitting that it's hard for anyone to ignore these extremely well-developed attention grabbing systems. These interruptions and distractions impair learning. Kids (and many adults) sincerely believe that they can multitask, and that it just takes them a moment to check that message and get back to the task at hand. The problem is that people engaged in multitasking end up doing their work at lower quality and taking more time to do it. (The best demonstration of this I've seen is this video activity by Dave Crenshaw. It's a great activity to do with students and/or teachers.) It is even more pronounced when the distraction has emotional significance, which for teenagers is just about any social media posting or message. Deep learning takes time. Uninterrupted, focused time. The next book on my reading list is called Deep Work, by Cal Newport. You can listen to a great interview with him about the topic on the podcast/radio program Hidden Brain. He presents compelling evidence that the more time we spend in busy, shallow work, the less capacity we have for doing truly meaningful deep work that requires focus and persistence. Being able to focus is a skill, and we need to practice it. That means we need to create environments where students are given the opportunity to regularly engage in a single task without interruption. (This is more than a smartphone issue, obviously. In your school schedule, what is the longest block of time that students get to spend working on just one thing?) One of the most critical skills to learn about technology is when to use it, and when not to. It is there to empower us, not overpower us. We all - children and adults alike - need to recognize when using technology interferes with learning, working, thinking, or even just carry on meaningful conversations. Or figuring out how to constructively respond to boredom without resorting to Facebook, Pinterest, or Candy Crush. I think one measure of just how important it is to separate students from their smartphones is how hard it is. It's not just the students; parents want to be able to contact their children whenever they feel the need. If we are all so habituated to these devices (and more importantly, the social media software that's on them) that being without them is upsetting, then it's time to admit to ourselves that we have a problem. If you're interested in discussing/exploring/arguing more about this topic, I'm doing a session at the NCCE conference on called Being a Well-Adjusted Cyborg - What Neuroscience Tells Us about Using Technology. I hope to see you there!  Last week I had the wonderful opportunity to attend the Surrey International Writers Conference in British Columbia with my dad and daughter. We and about 600 other people spent three days and evenings listening to great presentations by established authors, and talking with each other about every aspect of writing. It was fun, incredibly informative, and energizing. (If you want to go next year, bookmark the website and put a reminder on your calendar to register in May or June - it sells out early!) As I was reflecting on the experience this morning, it occurred to me that the reason this conference is so successful (25 years and counting) is that the entire experience from beginning to end is built on a growth mindset. The underlying assumption is "You can be a writer." Not necessarily a best-selling writer, or even a full-time professional writer, but a writer. And it's not just puffery; each day is jam-packed with very specific expert advice and tips on how to improve, and opportunities to sit down one-on-one with published authors and have them review your work ("Blue Pencil Sessions") with honest but constructive, specific feedback. Each and every presenter was positive, encouraging, and happy to share their techniques and strategies, whether in a presentation or if you just happened to end up in the elevator with them. (For those of you who enjoy the Outlander series, you'll be glad to know that Diana Gabaldon is just as friendly, personable, and incredibly smart as you imagine her to be.) The people in attendance represented authors and potential authors of every level and genre, but the underlying mindset was universal. No matter where you are, you can be even better - and here's how. I came away challenged not only as a writer, but as an instructor and presenter. I want to make sure my work consistently reflects the same strong and positive mindset. *This title is adapted from writer/performer Mary Robinette Kowal, who provided an amazing keynote delivered through one of her puppets, and her fuzzy companion referred to itself as a Metaphor Made Manifest. I am still unpacking the layers of emotional complexity of her writing, her performance, and the impact of using an imaginary intermediary to connect with the participants. I will also admit right here and now that I am already contemplating how I can get away incorporating a puppet into some future presentation, and I apologize in advance for so shamelessly stealing from her. |

Archives

October 2019

Categories

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed